For the past 12 months labour and transport experts from EU Member States gathered information and discussed the wide-spread phenomenon of Pay-to-Fly (P2F) schemes. Their conclusion is that P2F is bad and should be forbidden.

So far with the good news.

The bad news is that surprisingly the expert group found no P2F cases in Europe. This doesn’t mean that it does not exist. So why does P2F remain out of sight of authorities?

Since 2015, European Cockpit Association (ECA) has been campaigning for a ban on P2F in Europe. P2F is an industry practice whereby a professional pilot flies an aircraft on a regular revenue-earning flight – as any other qualified crewmember. But instead of receiving a salary the pilot pays the airline for the flight hours. ECA has flagged this abuse on every possible occasion. And after the EU Parliament took interest in such schemes already a few years ago, we were finally happy to see the group of Member States’ labour and transport experts investigating P2F schemes as an assignment from the European Commission. Despite the hard work of the expert group, however, we are exactly where we were in 2015: P2F continues to flourish hidden under the radar of authorities.

This is because, according to authorities, most cases of P2F are not within the scope of the investigating powers of labour inspectors. As long as the pilot is not employed by the airline during the P2F, the labour authorities cannot intervene. So, if an airline, a training school or recruitment agency asks a cadet to fulfill a course, which includes flight experience (e.g. line training) before employment, there is nothing that authorities can do, even if pilots have to pay for these flight hours. On the contrary, if an employment contract exists, it would be illegal to ask the pilots to pay for those flight hours. In this way, the airlines disguise the employment contract as a training contract – whereby an agency places the pilot to ‘train’ for a ‘partner airline’.

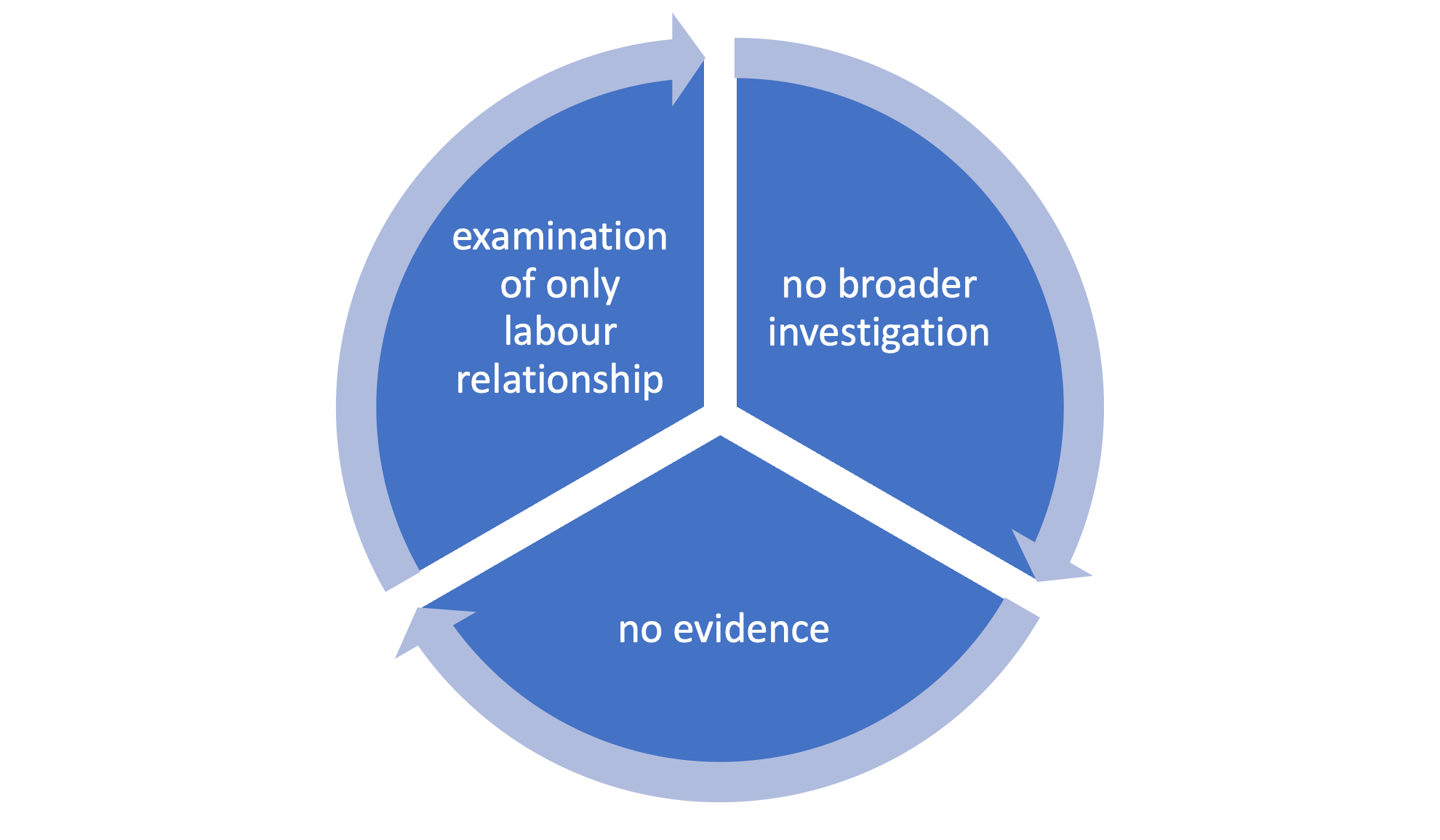

Another rather unfortunate consequence is that by narrowing the scope of P2F only to a labour relationship, the Member States make it impossible for their authorities to find cases in their countries. Thus, a vicious circle sets in: looking for P2F with an employment contract – no cases – no evidence – no investigation. No problem.

Meanwhile, P2F continues to be a problem and a common practice in European aviation. Cadets and young pilots, after graduating from flight schools and having already a pilot license, are forced to “unfreeze” their license by paying for flight hours with sums starting from 20.000 up to 80.000 EUR. Witness to that are multiple advertisements offering hours at a ‘partner airline’.

It is not acceptable to ask a young 20–22-year-old to pay such sums after they already paid significant sums for their flight school to obtain their license. Neither is it legitimate to make retentions from their salary when they have already contributed to the costs of their training. P2F cannot be considered as training since it is not performed under the continuous supervision of a trainer and the cost of training on a specific course used by the employer to perform its services should therefore be borne by the employer.

Authorities should examine P2F from a broader perspective. These authorities should be able to investigate any pilot, performing commercial operations for an airline, even in a training period. These practices are a straightforward disguised employment relationship which fall under the oversight of any aviation authority.

Ironically, those airlines that have turned the cost of training cadets into a source of revenue are the same ones complaining about pilot shortage. If they genuinely wish to find sufficient pilots, they should first consider offering them the training and a decent contract instead of making them pay to fly.